Chasing the ornaments cryptically away

In many insect species, male nuptial food gifts are sexually selectable traits, like eye color, wing size, body mass and pheromones. This visual trait conveys signals of male quality to females - in roughly a direct proportion to its size. Males in a bewildering number of insect species display items - such as salivary secretions, spermatophores, whole or parts of their bodies to females before, during or after copulation for females to consume. However - in general, the gift is offered by males before copulation to induce females into mating. [1, 2, 3]

Under orthodox models of sexual selection (SS): (1) a "direct benefit" to females, nuptial gifts provide valuable mating-incentives - as nutritional resources are scarce, severely lacking in many insect habitats, and (2) an "indirect benefit" to females, mating with gift-giving males maximizes their reproductive fitness - as (in most cases) males capable of producing these traits are "the more vigorous and fit" members of the male population.

By contrast - under a newer, chase-away model of SS, female attractions to male display traits may conflict with their reproductive fitness. When female preferences towards male traits turn against their reproductive interest, females, under the model, evolve bio-physical resistances to counter-act the disadvantages of selecting for the traits, and in the process, enhance their own reproductive fitness - at the expense of the males'.

In perhaps the most consequential SS experiment of recent memory, Cryptic Sexual Conflict in Gift-Giving Insects: Chasing the Chase-Away (2006), Sakaluk et al. isolated nuptial gifts from males of a gift-giving species of crickets, then - during mating trials, fed them to females of a non-gift-giving cricket species. This research was conducted to assay whether the onset of female remating is postponed by the consumption of gifts and to evaluate how their ingestion affects "classical", female reproductive fitness.

Females of the non-gift-giving species showed strong attractions towards the gifts - whereas females of the gift-giving species showed weak ones. When the gifts were consumed by females of the non-gift-giving species, their remating was delayed "significantly". In contrast - when females of the gift-giving species were deprived of gifts during mating, "there was no difference in their propensity to remate relative to females permitted to consume a food gift".

The researchers postulate that these gifts contain hormones - which regulate the speed of female remating. Subsequent research has born-out that over time, females of a number of species have developed "resistances" to male display traits by building-up defenses via "counteradaptations". Unlike females of the gift-giving species, females of non-gift-giving species never had the "evolutionary experience" to acquire immunity against the effects of the gifts, i.e. "antiaphrodisiacs"; hence, their remating has been shown to be delayed.

In terms of genetic fitness in polyandrous species, the delay of female remating is an advantage to males but a disadvantage to females. Delaying female remating reduces the probability that females will combine their genes with high(er) quality male genes (or combine them with a greater variety of male genes which maximizes the probability of their genes proliferating). Over a female's reproductive lifetime, decreasing her remating rate lowers her reproductive output and shifts the genetic profile of her offspring. By a multiplier effect on other females, slowing-down female remating lowers the reproductive output and shifts the genetic environment of the population. Such outcomes may shape the evolutionary trajectory of an entire species - unless the male-fitness-driven consequences of gift acceptance are "chased away" by concealed ("cryptic") female counter-measures.

Below are excerpts from: Cryptic Sexual Conflict in Gift-Giving Insects: Chasing the Chase-Away

- Scott K. Sakaluk, Rachel L. Avery, and Carie B. Weddle

-

"Holland and Rice (1998) proposed a new model to account for the evolution of elaborate male sexual displays that incorporates this fundamental conflict over mating rate. According to their model, display traits initially arise in males because they exploit preexisting sensory biases in females and consequently induce females to mate in a suboptimal manner. This in turn selects for female resistance or decreased attraction for the trait, which in turn leads to greater selection on males to exaggerate the display trait to overcome this resistance. The resultant cycle of antagonistic co-evolution forms the basis of what Holland and Rice (1998) and Rice (1998) term the "chase-away" model of sexual selection []"

"Nuptial food gifts, an integral feature of the mating systems of a wide variety of insects, may be a frequent conduit by which males attempt to influence the mating behavior of females against females' own reproductive interests."

"We believe that we have identified a male display trait that presents a unique opportunity to seek unequivocal evidence of female resistance and to demonstrate that female attraction to a male display trait can lead to decreased female fitness. The male display trait in question is a courtship food gift, the spermatophylax, a component of the spermatophore that is transferred by male decorated crickets Gryllodes sigillatus (Orthoptera: Gryllidae) to females at mating."

"When food gifts of male G. sigillatus were fed to females of a non-gift giving species, Acheta domesticus, females took significantly longer to remate than did females that were not given food gifts to consume after their initial mating. In contrast, when female G. sigillatus were prevented from consuming their partners' nuptial gifts, there was no difference in their propensity to remate relative to females permitted to consume a food gift after mating."

"[Acheta domesticus] Females provisioned with novel food gifts were "fooled" into accepting more sperm than they otherwise would in the absence of a gift, suggesting that food gifts evolve through a unique form of sensory exploitation."

"These results suggest that the spermatophylax synthesized by male G. sigillatus contains substances designed to inhibit the sexual receptivity of their mates but that female G. sigillatus have evolved reduced responsiveness (i.e., resistance) to these substances."

"If the evolution of the spermatophylax is explicable within the context of the chase-away model of sexual selection, it requires that males benefit by inducing a delay in remating by their mates and that females suffer a reduction in fitness from any such delay. There is clear evidence to support both of these underlying assumptions."

"To the extent that our data provide support to this interpretation, they have established a critical facet of the chase-away model, namely, that females frequently prevail in sexual conflicts, encumbering males with sexual display traits that often have little or no effect on female mating decisions (Holland and Rice 1998)."

On an historical note: Darwin conducted the first SS experiment. To prepare, he surgically blinded a control group of peahens. During the experiment, Darwin observed that the experimental (non-blinded) peahens exhibited a "preference" for mating with the "more ornamented" cock. He, also, observed that the control group females could not, after blinding, "choose" peacocks on the basis of the cocks' tails displaying "a gorgeous plumage" - due to their inability to receive visual stimuli.

"The females are most excited by, or prefer pairing with, the more ornamented males, or those which are the best songsters, or play the best antics; but it is obviously probable that they would at the same time prefer the more vigorous and lively males, and this has in some cases been confirmed by actual observation." -- Darwin [4]

Nuptial food gifts are another instance of Darwin's "male ornaments". However, the chase-away model differs from older SS models, derived more directly from Darwin's passage above - under which elaborate male traits convey "straight/honest/non-exploitative signals" of male quality to females. Under the chase-away model, it's expected that a detectable evolutionary history, consisting of a mutually "antagonistic co-evolution" between male and female reproductive strategies will emege in experiments, genetic research and possibly the fossil record.

Gould once wryly quipped that the rediscovery of sexual selection as a powerful evo-driver had to do with the social ramifications, stemming from the "Women's rights struggle of the 1960s". (For example - in the 1940s, zoologist, Julian Huxley, could not bring himself to admit that female birds exhibit mate preferences for "the more ornamented" males.) Gould may have been on to something regarding the early inspiration behind the relatively recent resurrection of SS, but experimental biology is bearing-out a complex, allele-level and hidden conflict, priming the evolutionary developments of female and male reproductive traits. Darwin, that most meticulous observer of non-human mating behavior, referring to a different passage in his Descent, may have chuckled, exclaiming: "Told ya so!".

"The courtship of animals is by no means so simple and short an affair as might be thought." -- Darwin

Females of many insect (and arachnid) species are predisposed by genetic factors and environmental cues to prefer mating with males - who display nuptial gifts. If females were shown never to have had a preference for nuptial gifts, evolutionary biologists would scratch their heads, wondering why (or how) this "male ornament" arose in nature. Darwin insisted that evolutionary theory would fail - if the existence of "male ornaments" (and female "preferences" for them) were not outcomes of sexual selection. Natural selection cannot explain the appearance and persistence of these traits on the part of male organisms - because they confer survival disadvantages. However - according to sexual selection, the ornaments confer reproductive advantages on the males, carrying them.

Under the chase-away model, females, over time, shift their preferences for male ornaments - when selecting for them counters their "reproductive interests". Such a shift is a weapon in the evolutionary "arms race" between males and females. Once females reduce their preference for a given male trait, males tend to intensify the size of the trait or alter their behavior (e.g. by displaying a different trait) to attract females into mating.

Notes

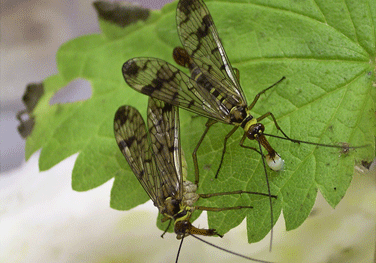

(1) From Nuptial food gifts influence female egg production in the scorpionfly Panorpa cognata

"Male provision of food gifts during courtship and copulation is widespread in insects. (Thornhill, 1976; Vahed, 1998) Nuptial food gifts may take the form of prey items, parts or the whole of the male body, as well as glandular secretions. (reviewed by Vahed, 1998) Within Panorpa, male production of salivary secretions on which females feed during copulation is widespread and possibly universal. (Thornhill, 1976; Vahed, 1998)"

"Before copulation, male Panorpa cognata scorpionflies offer females a salivary secretion, which is consumed by the female during copulation. It has previously been demonstrated that this nuptial food gift functions as mating effort by increasing male attractiveness and by increasing ejaculate transfer during copulation." -- Leif Engqvist

(2) From Male nuptial gifts: phenotypic consequences and evolutionary implications

"Much of the work on insect nuptial gifts has been done to explore the effects of relative reproductive investment by each sex on sex roles and the operation of sexual selection. This work was stimulated by a series of authors, beginning with Darwin."

"Male nuptial gifts are widespread across insect orders, including those with a range of feeding habitats and in a diversity of environments."

"Nuptial gift giving is an excellent vehicle to test sexual selection theory. Male nuptial gifts have primarily served as a case example to study theories of sexual selection."

"The antiquity of spermatophores within Insecta means that the potential for male nutrient donations via the spermatophore or similar accessory gland secretions is probably at least as old as the class." -- Carol L Boggs

- my note

- Nuptial gifts orginated as phenotypic sex traits in the Triassic - about 500 million years ago.

(3) From Foraging ability in the scorpionfly Panorpa vulgaris individual differences and heritability

"According to indicator models of sexual selection, mates may obtain indirect, i.e. genetic, benefits from choosing partners indicating high overall genetic quality by honest signals. In the scorpionfly Panorpa vulgaris, both sexes show mating preferences on the basis of the condition of the potential partners. Females prefer males that produce nuptial gifts (i.e. salivary secretions) during copulation, while males invest more nuptial gifts in females of high nutritional status." -- M. Missoweit, S. Engels and K. P. Sauer

(4) See: The Descent of Man (and Selection in Relation to Sex), by Charles Darwin

- Further reading

- Sexual Selection, sensory systems, and sensory exploitation - Michael L Ryan

- Nuptial feeding in the scorpionfly Panorpa vulgaris - Sierk Engels

- Leif Engqvist's bio and publication list

- Fluctuating Asymmetry and Variation in the Size of Courtship Food Gifts in Decorated Crickets - Eggert and Sakaluk

- A Drosophila male pheromone affects female sexual receptivity - Grillet, Dartevelle and Ferveur